This blog post is the third part of the Compact Deep Dive series, which explores how Compact contracts work on the Midnight network.

Each article focuses on a different technical topic and can be read on its own, but together they provide a fuller picture of how Compact functions in practice.

The first two parts can be found here:

This article looks at the on-chain runtime and how public ledger state updates happen in your DApp.

The Bulletin Board's post Circuit

In the previous parts we used the Bulletin Board example DApp to take a look at contract structure and the implementation of circuits and witnesses.

We saw that a contract's exported circuits, such as post from the Bulletin Board example, had an outer "wrapper" that called the actual implementation.

We will now take a look at that actual implementation.

Recall the Compact implementation of post:

export circuit post(newMessage: Opaque<"string">): [] {

assert(state == State.VACANT, "Attempted to post to an occupied board");

poster = disclose(publicKey(localSecretKey(), instance as Field as Bytes<32>));

message = disclose(some<Opaque<"string">>(newMessage));

state = State.OCCUPIED;

}

It reads the state field from the contract's public ledger state and asserts that the bulletin board is vacant.

Then it calls the witness localSecretKey and uses the return value to derive poster, a commitment to the post's author.

Finally, it updates three ledger fields (poster, message, and state).

We compiled the contract with version 0.25.0 of the Compact compiler.

Note that this is a different version than the one used in parts one and two of this series.

If you use a different version, the implementation details might be different.

The implementation of post is in a JavaScript function called _post_0.

Every line of this function has something new to learn about the way that Compact works, so we will go line by line through it.

The first line of this function corresponds to the first line of the Compact circuit:

_post_0(context, partialProofData, newMessage_0) {

__compactRuntime.assert(

_descriptor_0.fromValue(

Contract._query(

context,

partialProofData,

[

{ dup: { n: 0 } },

{ idx: { cached: false,

pushPath: false,

path: [

{ tag: 'value',

value: { value: _descriptor_9.toValue(0n),

alignment: _descriptor_9.alignment() } }] } },

{ popeq: { cached: false,

result: undefined } }]).value)

===

0,

'Attempted to post to an occupied board');

(Here and below we have reformatted the JavaScript code to fit better on screen. The only change is the indentation.)

We will read this line of JavaScript from the inside out.

The very first subexpression evaluated in the Compact post circuit is simply state, which is a read of the ledger's state field.

This also must be the first thing evaluated in the JavaScript implementation.

It is implemented by a call to a compiler-generated static method _query on the Contract class.

(We will take a closer look at Contract._query in the next article in this series.)

Recall what is happening when _post_0 is executed in your DApp.

The JavaScript code is running locally on a user's machine, with full access to private data from the witnesses it uses.

After running the code, the proof server will be used to construct a zero-knowledge (ZK) proof that it did run that code.

Then, a transaction will be submitted to the Midnight chain.

If the chain verifies the proof, the public ledger state updates specified by the circuit implementation will be performed.

The Midnight node uses the Impact VM,

a stack-based virtual machine, to perform public ledger state updates.

This machine executes a program in a bytecode language called Impact.

We use the same Impact VM to perform updates to a local copy of the public state when we are running your DApp's code locally before submitting a transaction.

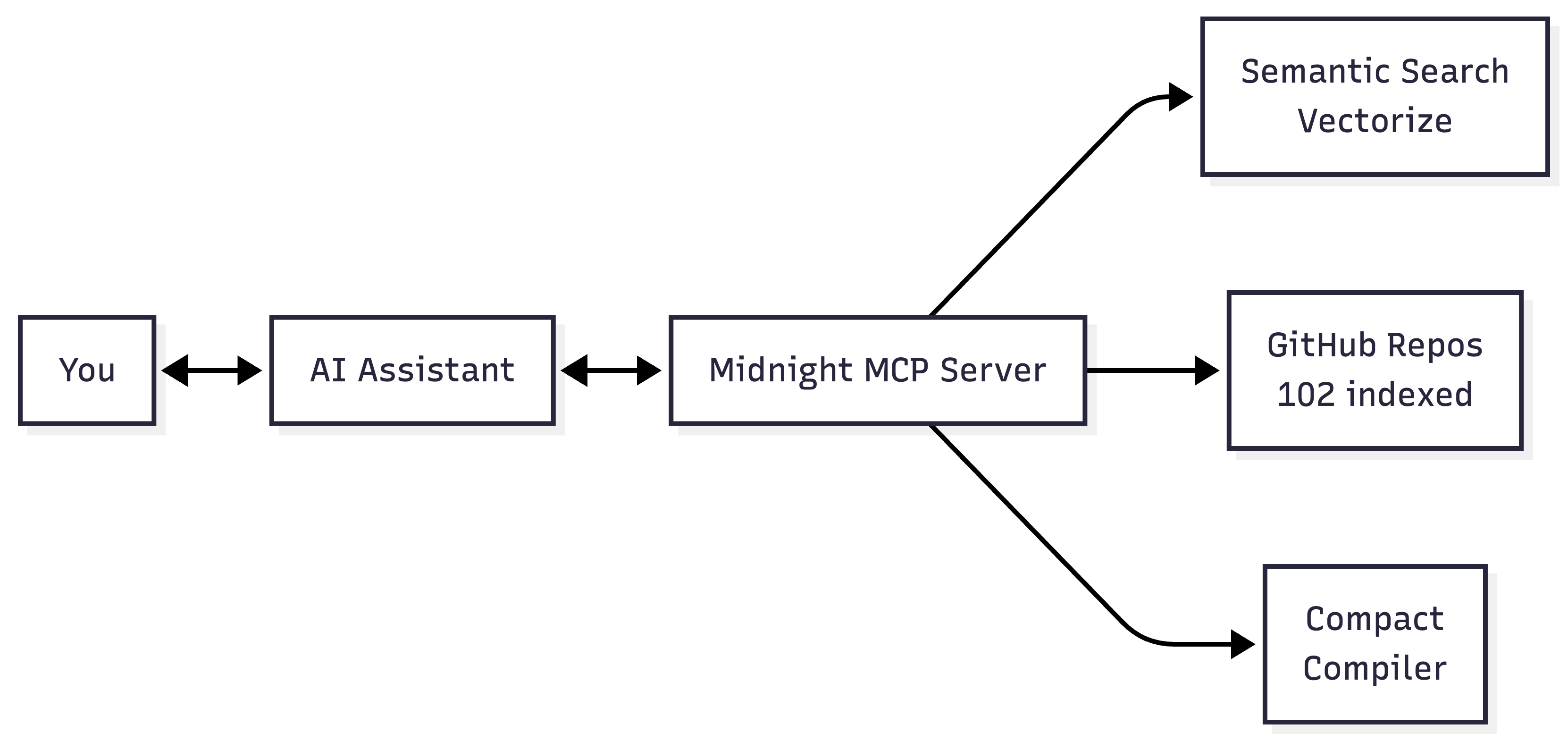

The On-Chain Runtime and the Impact VM

The Compact runtime package includes an embedded version of the on-chain runtime.

This is the exact same Rust code that is used to implement the Midnight ledger on the Midnight network nodes.

For the Compact runtime, it is compiled to WebAssembly and imported as the on-chain runtime package.

You can actually use this package directly in your DApp, though much of it is re-exported by the higher-level Compact runtime.

Sometimes the Compact runtime provides wrapped versions that have a higher-level API

(specifically, using JavaScript representations instead of the ledger's native binary representation).

If you use the on-chain runtime package directly in your DApp, it is very important to remember that you are working with a snapshot of the public state.

This snapshot was obtained from a Midnight indexer, but while your DApp is running, the chain itself is progressing with other transactions for the same contract.

That's part of what it means for a DApp to be "decentralized".

The Impact VM performs public ledger state updates, immediately in your DApp's copy and later (when the transaction is run) on chain.

There are a host of reasons to use the exact same VM:

- Transaction semantics will be identical.

- It saves engineering work to implement it (and update it and maintain it) once.

- We will need the Impact program to compute fees for the transaction.

- The ZK proof will be about this specific Impact program.

The Impact VM is a stack-based machine.

Transactions operate on a stack of values, which are encoded in the ledger's binary representation.

The transaction always starts with three values on the stack:

- First (at the base of the stack), a context object for the transaction.

- Second, an effects object collecting actions performed by the transaction.

- Third, the contract's public state.

When a transaction completes, these three values are left on the stack in the same order.

Values on the VM's stack are immutable.

For instance, a state update is accomplished by replacing the state third on the stack with a new one

(rather than mutating the existing state value).

The third argument to Contract._query is an array of Ops which are JavaScript representations of Impact VM instructions.

Op is a type defined in the on-chain runtime.

Transactions will use a binary encoding of these instructions.

The array of instructions is a partial Impact program.

A whole program will be built up for the transaction, usually with multiple calls to Contract._query.

Ledger Read Operations

The Impact code for the ledger read of the field state from above was:

[

{ dup: { n: 0 } },

{ idx: { cached: false,

pushPath: false,

path: [

{ tag: 'value',

value: { value: _descriptor_9.toValue(0n),

alignment: _descriptor_9.alignment() } }] } },

{ popeq: { cached: false,

result: undefined } }]

The first instruction is dup 0.

Instructions will find their inputs on the Impact VM's stack.

They can also have operands which are encoded as part of the instruction, such as the zero in dup 0.

The dup N instruction duplicates a value on the stack.

The value is found N elements below the top of the stack, so N=0 is the top of the stack.

Since this is the first Impact instruction in a post transaction, that will be the public ledger state value.

Before dup 0, the Impact VM's stack had <context effects ledger0> in order from the base to the top of the stack.

ledger0 is the initial ledger state of this transaction.

After dup 0, it will have <context effects ledger0 ledger0> with two copies of the ledger state on top of the stack.

This allows subsequent instructions which consume values to execute without losing the public ledger state.

The second instruction is idx [0].

This instruction indexes into the top value on the stack, extracting a subpart of it.

It removes the top value on the stack and replaces it with the extracted subpart.

The instruction's operand is a path, a sequence of ledger-encoded values (or a special tag stack).

The two different encodings of values, and the descriptors that convert between them, were described in Part 2.

Here the instruction uses _descriptor_9:

const _descriptor_9 = new __compactRuntime.CompactTypeUnsignedInteger(255n, 1);

This is an instance of CompactTypeUnsignedInteger

from the Compact runtime.

It takes a maximum value and a size in bytes.

So this is the descriptor for a one byte unsigned integer with a maximum value of 255 (that is, just an unsigned byte).

The value 0n is the public ledger state index that the Compact compiler has assigned to the state field.

Impact has four different indexing instructions: idx, idxc (cached), idxp (push path), and idxpc (push path, cached).

In the JavaScript representation of instructions, we simply use a pair of boolean properties giving the same four variants.

cached is true when the value being accessed has already been accessed (that is, read or written) in the same transaction.

It can potentially be used for assigning different fees for cached and uncached accesses.

In this case, we have not accessed the state ledger field yet in the transaction.

pushPath is a variant that leaves a path in place on the stack for a subsequent write operation.

Before idx [0], the VM's stack had <context effects ledger0 ledger0>.

After idx [0], it will have <context effects ledger0 state> (where ledger0 is the entire public ledger state and state is the value of the field with that name).

The third instruction is popeq.

This instruction pops the top value from the VM's stack.

The Impact VM can run in two different modes.

It runs in gathering mode when it runs locally in a DApp.

It runs in verifying mode when it executes a contract's public ledger state updates on chain.

In gathering mode the popped value is collected (it's used by Contract._query as the result of this ledger read).

In verifying mode the VM will ensure that the popped value is equal to the instruction's operand.

Here we are running in gathering mode, so the instruction's result operand is the JavaScript undefined value.

Before popeq, the VM's stack had <context effects ledger0 state>.

After popeq, it will have <context effects ledger0>.

These three simple VM instructions implement a top-level ledger read.

Assert in Circuits

The post circuit asserts that the bulletin board's state is vacant.

This is implemented by the JavaScript code from above (with the Impact instructions elided):

__compactRuntime.assert(

_descriptor_0.fromValue(

Contract._query(

context,

partialProofData,

).value)

===

0,

'Attempted to post to an occupied board');

Contract._query returns an object with a ledger-encoded result.

_descriptor_0 is the descriptor for the the State enumeration type, so _descriptor_0.fromValue is used to convert it to one of the enumeration values VACANT=0 or OCCUPIED=1.

This value is compared via JavaScript's strict equality operator to the vacant value (zero).

The assertion itself is implemented by a call to the Compact runtime's assert function.

If the condition is not true, this will cause the DApp's post transaction to fail without ever reaching the Midnight chain.

Provided that the assertion succeeds when running the DApp locally, the ZK proof will prove that it suceeded.

When the proof is verified on chain, the Midnight network will then know that this assertion was true.

The on-chain Impact program will not directly assert this property (that state was State.VACANT).

However, when the popeq instruction is run in verifying mode, it will have an operand that indicates the actual value that was popped locally in the DApp.

So specifically, if the DApp successfully built a post transaction, that instruction will be popeq 0.

This is subtly different from asserting that the state field was 0.

If the assert were removed from the Compact program and the ledger field read remained,

then the Impact program run on chain could have either popeq 0 or popeq 1 depending on the actual value that was read by the DApp.

Circuit and Witness Calls

The second line of the Compact post circuit is:

poster = disclose(publicKey(localSecretKey(), instance as Field as Bytes<32>));

This is a write to the ledger's poster field.

The right-hand side of the write operation is implemented by the JavaScript code:

const tmp_0 = this._publicKey_0(

this._localSecretKey_0(context, partialProofData),

__compactRuntime.convert_bigint_to_Uint8Array(

32,

_descriptor_1.fromValue(

Contract._query(

context,

partialProofData,

[

{ dup: { n: 0 } },

{ idx: { cached: false,

pushPath: false,

path: [

{ tag: 'value',

value: { value: _descriptor_9.toValue(2n),

alignment: _descriptor_9.alignment() } }] } },

{ popeq: { cached: true,

result: undefined } }]).value)));

The compiler has named this value tmp_0 so it can refer to it later.

The call to the witness localSecretKey has been compiled into a call to the _localSecretKey_0 method of the contract.

Recall from Part 2 that this method is a wrapper around the DApp-provided witness implementation.

The wrapper performs some type checks on the witness return value, and it records that return value as one of the transaction's private inputs.

The Impact code above implements the read of the ledger's instance field.

It is nearly the same as the code for the read of state.

The difference is that the Compact compiler has assigned instance to index 2.

The field instance has a Counter ledger type.

Reading it in Compact gives a Uint<64>.

The ledger representation of this value is converted to the JavaScript representation (bigint) using _descriptor_1:

const _descriptor_1 = new __compactRuntime.CompactTypeUnsignedInteger(18446744073709551615n, 8);

The maximum value here is the maximum unsigned 64-bit integer and the size in bytes is 8.

Type Casts in Compact

The Compact code has a sequence of type casts instance as Field as Bytes<32>.

instance is a Counter, reading it from the ledger gives a Compact value with type Uint<64>.

This cannot be directly cast to Bytes<32> so the contract uses an intermediate cast to Field.

There are three distinct kinds of type casts in Compact: upcasts, downcasts, and so-called "cross casts".

An upcast is from a type to one of its supertypes.

Such a cast will change the static type as seen by the compiler, but it will have no effect at runtime.

For example, casting from Uint<64> to Field is an upcast.

That cast was performed statically (that is, by the compiler) but there is no JavaScript code here to implement it.

A downcast is from a type to one of its subtypes.

Such a cast will not normally change a value's representation, but it will require a runtime check in the compiler-generated JavaScript code.

A cross cast is from a type to an unrelated type (with respect to subtyping).

For example, casting a Field to Bytes<32> is a cross cast.

These type casts will normally require a representation change.

The Compact runtime function convert_bigint_to_Uint8Array

performs the representation change in this case.

Then there was a call in Compact to the circuit publicKey.

Here we see that the call goes directly to the JavaScript implementation method _publicKey_0, and not to the exported circuit's publicKey wrapper.

Recall from Part 2 that the circuit wrapper performed some runtime type checks that we do not need when we call from Compact to Compact

(the Compact type system guarantees that these checks aren't needed).

More importantly, a circuit's wrapper established a fresh proof data object for a transaction.

Since the call to publicKey is part of the post transaction that the DApp is building, it should reuse the existing proof data.

Notice that the disclose operator in Compact doesn't do anything at all at runtime.

disclose was necessary because a value computed from the witness localSecretKey was exposed on chain.

This is an instruction to the Compact compiler to allow this value to be exposed, but it has no runtime effect.

Ledger Writes

The right-hand side value named tmp_0 in JavaScript should be written to the ledger field poster.

The code to do that is in the next line of JavaScript code:

Contract._query(

context,

partialProofData,

[

{ push: { storage: false,

value: __compactRuntime.StateValue.newCell(

{ value: _descriptor_9.toValue(3n),

alignment: _descriptor_9.alignment() }).encode() } },

{ push: { storage: true,

value: __compactRuntime.StateValue.newCell(

{ value: _descriptor_2.toValue(tmp_0),

alignment: _descriptor_2.alignment() }).encode() } },

{ ins: { cached: false, n: 1 } }]);

This is again implemented by a partial Impact program.

The Impact code above implements a ledger cell write (in contrast to the read we saw above).

The first instruction is push 3.

Impact's push instruction is the dual to the pop instruction.

Impact has two different variants: push and pushs.

In the JavaScript representation of Impact instructions, they are distinguished by a boolean storage property.

storage is false to indicate that the value is kept solely in the Impact VM's memory and will not be written to the ledger.

The second instruction is pushs tmp_0.

The instruction is pushs because storage is true (this value will be written to the ledger).

The instruction's operand will be the actual Bytes<32> value of tmp_0.

As you would expect, _descriptor_2 is the descriptor for Bytes<32>, used to convert the JavaScript value to a ledger value:

const _descriptor_2 = new __compactRuntime.CompactTypeBytes(32);

Before executing these two instructions, the Impact VM's stack had <context effects ledger0>.

After executing these two instructions, it will have <context effects ledger0 3 tmp_0>.

The next instruction is ins 1 which inserts into a value on the VM's stack.

Impact's ins instruction is the dual to the idx instruction we saw used for ledger reads.

The value to insert is on top of the stack (that is, the Bytes<32> value of tmp_0).

Underneath that is a path consisting of N elements, where N is the operand of the ins instruction.

In this case, the path has length 1, so it is the singleton sequence [3].

This is the index the Compact compiler has assigned to the top-level ledger field poster.

The insert instruction removes the value under the path (namely, the public ledger state)

and replaces it with a new copy of that value with the location denoted by the path updated to have the new value.

Before ins 1, the Impact VM's stack had <context effects ledger0 3 tmp_0>.

After ins 1, it will have <context effects ledger1> where ledger1 is a new public ledger state representing the write to poster.

The remainder of _post_0 has two more ledger writes and a return of the Compact empty tuple represented by the JavaScript empty array:

const tmp_1 = this._some_0(newMessage_0);

Contract._query(

context,

partialProofData,

[

{ push: { storage: false,

value: __compactRuntime.StateValue.newCell(

{ value: _descriptor_9.toValue(1n),

alignment: _descriptor_9.alignment() }).encode() } },

{ push: { storage: true,

value: __compactRuntime.StateValue.newCell(

{ value: _descriptor_5.toValue(tmp_1),

alignment: _descriptor_5.alignment() }).encode() } },

{ ins: { cached: false, n: 1 } }]);

Contract._query(

context,

partialProofData,

[

{ push: { storage: false,

value: __compactRuntime.StateValue.newCell(

{ value: _descriptor_9.toValue(0n),

alignment: _descriptor_9.alignment() }).encode() } },

{ push: { storage: true,

value: __compactRuntime.StateValue.newCell(

{ value: _descriptor_0.toValue(1),

alignment: _descriptor_0.alignment() }).encode() } },

{ ins: { cached: false, n: 1 } }]);

return [];

Take a look and see if you can see how the code above works.

publicKey

There is one more way that the on-chain runtime is used by Compact.

If we take a look at the implementation of the publicKey circuit (the actual implementation, not the wrapper for the exported circuit):

_publicKey_0(sk_0, instance_0) {

return this._persistentHash_0([new Uint8Array([98, 98, 111, 97, 114, 100, 58, 112, 107, 58, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]),

instance_0,

sk_0]);

}

We see that the padded string literal has been compiled to an explicit Uint8Array.

We also see a call to a _persistentHash_0 method, which is the Compact standard library's persistentHash circuit.

The compiler has included a JavaScript implementation of this circuit:

_persistentHash_0(value_0) {

const result_0 = __compactRuntime.persistentHash(_descriptor_7, value_0);

return result_0;

}

This is a call to the Compact runtime's persistentHash function.

This function in the Compact runtime is a thin wrapper around the on-chain runtime's own persistentHash.

The difference is that the on-chain runtime's version operates on the ledger encoding of values,

and the Compact runtime's version uses the descriptor it is passed to do the relevant conversion.

So this is the final capability of the on-chain runtime that we will look at here:

it contains implementations of functions like persistentHash that are shared between the DApp and the Midnight node.

In the next article in this series, we will look at how partial Impact programs get collected together

and how the compiler-generated JavaScript code produces so-called public inputs and public outputs for the ZK proof that will be generated.